While oligodendroglioma is a relatively rare brain tumor, accounting for 1.2% of all primary brain tumors, an estimated 14,950 Americans are living with this tumor and navigating the unique challenges of this disease.

Let’s talk about what makes oligodendrogliomas different from other brain tumors and the difficulties people living with this tumor type and their loved ones face every day.

Biomarkers Define Oligodendroglioma

For patients with oligodendroglioma, knowing their tumor’s biomarkers can mean the difference between an inaccurate diagnosis and a treatment plan tailored for the best possible outcome. Without biomarker testing, an oligodendroglioma could be misclassified as a different type of glioma, such as astrocytoma, which has a different prognosis and treatment approach.

“You’ve got to get those biomarkers because it can change the trajectory of your life,” said Kim M., whose husband was initially misdiagnosed with a higher-grade tumor before ultimately being diagnosed with oligodendroglioma. “We were initially told there was nothing we could do. Upon receiving our biomarker testing results six weeks later, we learned it was oligodendroglioma, and there were things that we could do.”

Through the MyTumorID public health campaign, the National Brain Tumor Society (NBTS) is raising awareness about the importance of biomarker testing, which plays a crucial role in diagnosing and treating oligodendroglioma. Additionally, it helps inform patients and their loved ones about mutations that could open up future clinical trial options.

“[We were told] you’ve got these mutations that when [the tumor] comes back, there are some clinical trials that are giving positive results on recurrent tumors,” Kim said.

Two key biomarkers define oligodendrogliomas.

IDH Mutation

Every oligodendroglioma has a mutation in the IDH1 or IDH2 gene, a genetic alteration in one of the isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) genes, which play a role in how cells produce energy and grow.

Did You Know? NBTS funding led to the discovery of the IDH mutation, which has become a critical means for neuro-oncologists to distinguish between different gliomas.

1p/19q Co-deletion

The 1p/19q chromosomal co-deletion is the loss of the short (p) arm of chromosome 1 and the long (q) arm of chromosome 19. This co-deletion is required for a definitive oligodendroglioma diagnosis.

“What the 1p/19q co-deletion represents is an expectation that the patient should be responding well to an alkylating chemotherapy agent,” said Ashley Ghiaseddin, MD, chief of the division of neuro-oncology in the University of Florida’s Department of Neurosurgery.

Did You Know? NBTS funding directly supported the discovery of the 1p/19q chromosome co-deletion, which is the key characteristic for identifying and diagnosing low-grade gliomas, including oligodendrogliomas.

Management of Oligodendroglioma

Treatment for oligodendroglioma depends on several factors, including the tumor’s grade, size, location, and symptoms.

When safe to do so, the primary treatment for oligodendroglioma is surgical resection to remove as much of the tumor as safely possible. A gross total resection (removing all visible tumor tissue) is ideal but not always achievable, especially for tumors near critical brain structures.

Chemotherapy and/or radiation may be needed if surgical resection is not possible, if tumor cells remain after surgery, or if the tumor is high-grade. Every treatment decision involves weighing the benefits of slowing tumor growth against the potential long-term side effects.

“When my husband was diagnosed in 2010, he did chemo for 12 months,” said Lauren*. “We went through the emotional rollercoaster of, ’I hate this medicine. I wish I didn’t have to take this medicine.’ And then we get to the final cycle where the care team says, ‘Okay, you’re done.’ And then we deeply regret stopping because doing something, it turns out, is easier than not doing anything. And that feels completely backward.”

Since oligodendroglioma often affects younger individuals — most commonly diagnosed in individuals between the ages of 35 and 44, according to the National Cancer Institute — factors like career, family planning, and cognitive function play a significant role in treatment choices.

The “Watch and Wait” Approach

Due to the slow-growing nature of these tumors, patients may follow a “watch and wait” approach before treatment is recommended. However, this period of uncertainty can bring its own challenges, from concerns about long-term health impacts of their treatment to scanxiety.

Regardless of whether a patient decides to pursue treatment upfront or not, people living with oligodendroglioma typically undergo frequent medical imaging for the rest of their lives — often at an interval of every 6-12 months.

“That can be very difficult [for patients] to realize that I’m always going to be at some risk that this may come back, and that waiting process can weigh on people, especially with such a young patient population,” Dr. Ghiaseddin said.

This “watch and wait” approach aims to preserve quality of life for as long as possible, delaying potential side effects from treatments like chemotherapy and radiation. On the other hand, starting treatment may help control the tumor’s growth but can lead to significant, lasting side effects.

This balancing act — preserving one’s current quality of life and proactively treating the tumor — makes decision-making incredibly complex, and is why it’s so important for patients to discuss their goals of care with their provider.

“I tried on one decision and then switched my mind and tried on the other decision to see how it felt over the course of a day or so,” said Alexandra B., who was diagnosed with oligodendroglioma in 2019. “I was trying to make sure that the choice I made was the right choice for me at that time. Struggling with figuring out what the best thing for you to do in totally unknown circumstances is not something I wish on anybody. It’s really hard.”

New Drug Approval

In 2024, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved vorasidenib for adults and pediatric patients (12+) with grade 2 astrocytoma or oligodendroglioma harboring an IDH1 or IDH2 mutation. This milestone marked the first-ever FDA-approved systemic therapy for these low-grade gliomas, offering patients a new option beyond traditional chemotherapy and radiation.

“It gives an opportunity for patients to potentially delay chemo [and] radiation in the right patient population so that they can take this medication with hopes that we’re delaying that time to next intervention or time to progression,” Dr. Ghiaseddin said. “Previously, you would look at somebody who had no visible tumor left after surgery, and you’d say we can watch this individual with an oligodendroglioma. If they had some residual tumor, there [are] a lot of factors that may have made you consider observation, but many times, those patients were doing some form of treatment that was radiation or chemotherapy or a combination thereof. Now, at least we have something that’s not chemotherapy that’s very well tolerated.”

Vorasidenib represents an additional option for doctors to manage these tumors.

“We’re not trying to tell anyone that this is better than chemo or radiation because we realize that those are very effective treatments,” Dr. Ghiaseddin added. “This is a patient population that, thankfully for our community, [usually] lives well and lives a long time, so we have to be careful when we want to give patients treatments like chemotherapy and radiation. They’re likely going to have side effects later on in life — related to those treatments — and they’re not inconsequential.”

Did You Know? NBTS played multiple roles in advancing this new treatment, including funding Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center-supported laboratory work that helped propel this research from a phase II to a phase III trial.

Oligodendroglioma Symptoms & Side Effects

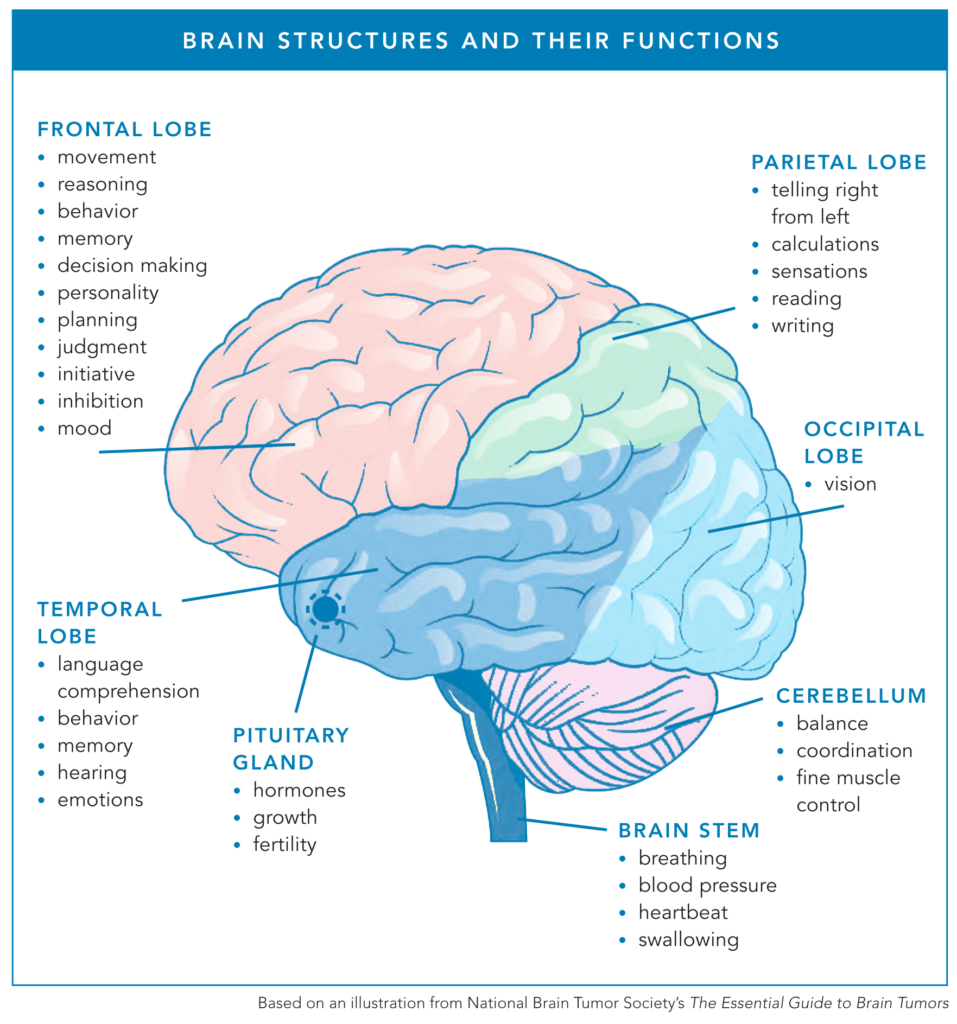

Oligodendrogliomas can develop anywhere in the brain but commonly occur in the frontal and temporal lobes. Because these regions control functions such as movement, memory, decision-making, and emotional regulation, symptoms can vary from patient to patient.

Dr. Ghiaseddin frequently sees his patients deal with seizures, headaches, forgetfulness, fatigue, cognitive slowing, and subtle weakness or numbness if the tumor involves the motor strip or sensory area.

“With his tremor, he can’t carry a cup of coffee that doesn’t have a lid on it,” Kim explained. “He can’t carry a plate of food without shaking it. Some days are better than others, but some days he’s not able to carry that plate.”

For many, the first signs of an oligodendroglioma can be subtle — often explained away or attributed to stress or aging. However, as the tumor progresses, symptoms can become more apparent.

“The biggest long-term issues are probably fatigue and memory, depending on the location,” Dr. Ghiaseddin said. “Many patients have some residual weakness [and] balance troubles so that they have more difficulty with their activities of daily living.”

Lauren*, whose husband’s tumor was located in the frontal and temporal lobes, describes how it impacts his ability to communicate and process information.

“My husband is the worst person in the world to leave a message with,” she explained. “That example seemed to be something that resonated with people.”

Seizures

Seizures are one of the most common and often the first symptoms of oligodendroglioma. According to the National Cancer Institute, seizures are the most frequent sign of the disease, and research published in CNS Oncology reports that seizures “represent the first clinical symptom in 60% of cases or more,” with epilepsy developing in 70–90% of oligodendroglioma cases.

“I would list seizures at the top of symptoms that patients may have,” Dr. Ghiaseddin said. “With the more aggressive glioma types, you may have someone present with a very violent, generalized seizure — first time ever — and they go to the ER. With oligodendrogliomas, it may be that they’ve had a few seizures, but they were short, small, and they weren’t generalized. Maybe there was ongoing workup happening, and the imaging wasn’t yet done, or they were getting to that point.”

Seizure management is often an ongoing journey that requires balancing anti-seizure medication effectiveness with side effects, adapting to new lifestyle limitations, and working with their health care teams to find the best approach for long-term care.

Fatigue

People living with oligodendroglioma may have to navigate physical and/or cognitive fatigue. Physical fatigue drains the body, leading to heaviness, weakness, and difficulty with physical tasks.

“There are things that he can’t do around the house because if he does them at the end of the day, he doesn’t have the energy to get up the next day,” Kim explained.

Cognitive fatigue impacts the mind, making it harder to focus, remember, or think clearly.

“I would say that mental fatigue — problems with multi-tasking and memory — are probably the hardest because [with] physical fatigue, you can sometimes be able to adjust for that or accommodate,” Dr. Ghiaseddin said. “I think it’s much harder with the mental fatigue for people to be able to accommodate to continue working.”

This cognitive or mental fatigue can make even simple decisions feel overwhelming, especially as the day goes on and the brain becomes more taxed.

“The neural fatigue is the biggest one for us because it impacts decision-making,” Kim said. “Word choice is hard for him at the end of the day, so it makes communication at the end of the day sometimes challenging.”

Scanxiety

For people living with oligodendroglioma, routine MRIs and other medical scans are a necessary part of managing the disease. However, with each scan comes scanxiety — the stress, worry, and emotional toll that can surface before, during, and after imaging. The uncertainty of what the results may reveal, combined with the ever-present fear of tumor progression, makes scanxiety a common and deeply personal challenge.

“I think in this population, you do get more depression, anxiety, and scanxiety,” Dr. Ghiaseddin said. “You can sometimes see patients even push out their appointment.”

For many, scanxiety isn’t just about the test itself — it’s a stark reminder of the reality of living with a brain tumor.

“The anxiety before a scan is the reminder that I have a brain tumor and that more than likely the brain tumor will be what ends my life,” said Brett J., who was diagnosed with oligodendroglioma in 2009. “These scans are to find out if the tumor is active or not. As I get closer — usually a few weeks — I face the reality that this brain tumor could kill me, and this scan is a marker. That’s what scans do. They remind you that everything could change on a dime today.”

For some, the lead-up to a scan brings sleepless nights, racing thoughts, or feelings of dread.

“At the beginning, I was out of my mind scared with every MRI,” Alexandra shared. “I was taking Ativan before every MRI. I still get anxious leading up to scans, but not quite as much as I used to. Scanxiety is definitely an unpleasant side effect.”

Caregivers, too, experience scanxiety as they wait alongside their loved ones for answers.

“For a good two weeks before the MRI and until we get the results, I am scared to death, and it’s horrible,” Kim said. “They talk about scanxiety for people. As a caregiver, I have it, but he doesn’t. I just am terrified the whole time.”

For patients struggling with scanxiety, there are actions they can take to cope, including self-care.

“I had a scan this week, and I definitely had scanxiety,” said Casey W., who was diagnosed with oligodendroglioma in 2010. “I had a hard time sleeping this week, and it was on my mind and my heart very much so. During the weeks that I have scans, I try to stay occupied with work and spend extra time with my three small kids.”

Living with Oligodendroglioma as a Young Adult

For young adults, living with oligodendroglioma presents a unique set of challenges. Oligodendrogliomas are frequently diagnosed between the ages of 35 and 44, an age range where many are focused on career advancement and raising children. This early diagnosis often comes with significant obstacles that impact a person’s daily life and sense of stability.

“I was actually scheduled to start my [first-ever] full-time job 10 days after my surgery,” Casey said. “I just remember feeling embarrassed, feeling why me. I was young and naive.”

For young adults with an oligodendroglioma diagnosis, it can mean navigating a combination of physical and cognitive challenges while managing the demands of work, family, and treatment.

Employment

Surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation can cause side effects that impact cognitive function, memory, and energy levels, which can affect one’s ability to work.

Alexandra, a pediatrician diagnosed at age 36, explained how her dream job was no longer viable once treatment began.

“The job that I loved was lost the moment that I had my MRI,” Alexandra explained. “Part of it was my chemotherapy and side effects, and from a scheduling perspective, there was no way for me to be on the schedule in a predictable week. It’s hard to plan around the uncertainty of what may happen with each scan.”

As Dr. Ghiaseddin noted, many patients, even those who have lived with oligodendroglioma for years, struggle to continue working due to fatigue and cognitive challenges.

“I would say the majority of patients that I see who are 10 years out from a diagnosis — even one like oligodendroglioma — aren’t working after that time,” Dr. Ghiaseddin said. “They have to usually quit their job because the fatigue and memory component really makes it more difficult for them to be able to do that.”

Parenting

For parents with a child or children still living in the home, an oligodendroglioma diagnosis brings not only personal uncertainty but also challenges in helping children process complex emotions. Balancing treatment, work, and daily responsibilities while ensuring children feel secure can seem overwhelming. Many parents living with a brain tumor find that open communication is key in helping their children cope.

“It has been difficult to help the kids work to understand their emotions surrounding this experience, but one thing my wife and I have encouraged our kids to do is to feel their feelings,” said Kasey T., who has grade 3 oligodendroglioma. “We make sure to let them know it is OK to be scared, sad, or angry sometimes. We encourage them to share their feelings with us and let them know that it is OK to feel.”

Children often struggle with the unpredictability of a parent’s health, which can lead to anxiety and worry. Alexandra, a pediatrician and parent living with oligodendroglioma, emphasized the importance of acknowledging these emotions openly.

She said, “It’s scary for everybody. Just acknowledge that and let the kids know that you’re scared too sometimes, and it’s OK to be scared, and that’s a normal way to feel. Let them have the space to talk about it without feeling any shame or embarrassment for being scared of something like that.”

Hope Through Research

For people living with oligodendroglioma, the reality is that their tumor will likely return at some point. Knowing this, patients and their loved ones often become passionate advocates for research, hoping that by the time their tumor recurs, better options will be available.

“They caught my tumor very early,” Brett shared. “My doctor said that when my tumor grows back, I’ll have a lot of arrows in my quiver. The longer I live, the more options there will be for treatment. It’s one of the reasons I come back to NBTS every year, because they are committed to the kind of research that gives me hope for a longer future.”

Since 2013, NBTS has funded more than $2 million in grants to 16 researchers across 12 different institutions, all benefitting oligodendroglioma and related low-grade glioma research.

Recently, NBTS has focused on creating high-quality lab models to study these tumors better. Oligodendroglioma cell line models are essential tools to advance research and drug development. Think of these cell models as a key element in a drug proving ground — a controlled environment in the lab where scientists can rigorously vet potential therapies before they reach clinical trials.

Historically, preclinical research has been limited due to a lack of useful oligodendroglioma cell lines. Through the DNA Damage Response Consortium, NBTS has helped secure and optimize new oligodendroglioma cell lines, allowing scientists to test treatments faster and more effectively.

With limited industry investment in low-grade glioma research, including oligodendroglioma, the burden of funding early-phase clinical trials often falls on the federal government. Without this funding, promising treatments would struggle to move forward, delaying progress for patients who urgently need better options. That’s why NBTS is working relentlessly to shine a light on this critical need and advocate for increased federal funding through the National Cancer Institute (NCI).

NBTS’s ongoing advocacy efforts, including its annual Head to the Hill event, ensure that brain tumor research remains a national priority. By pushing for federal research funding, directly supporting innovative research, and providing patient navigation and support, NBTS is driving progress on all fronts to bring better treatment options and improved quality of life to people living with oligodendroglioma.

* Note: NBTS altered this patient’s name to protect the privacy of the quoted individual.