A person’s first seizure can be a disorienting experience — their body may tense up or convulse, their mind may go blank, or they may start talking incoherently. And then just as suddenly as it began, it’s over. For some, that single moment becomes the first step toward an unexpected diagnosis: a brain tumor.

Frontiers in Surgery reports that seizures can be the first presenting symptom before a diagnosis in approximately 30-60% of patients with primary brain tumors, depending on the type of tumor.

Learn more about seizures caused by brain tumors and find answers to frequently asked questions below.

Why do brain tumors cause seizures?

Brains run on electrical signals that help neurons (brain cells) communicate. A brain tumor can irritate the nearby brain tissue and interfere with the normal electrical activity, leading to a seizure. During a seizure, there’s a sudden surge or overload of abnormal electrical activity, which can temporarily disrupt the normal flow of information, like a power surge knocking out a circuit.

According to the Handbook of Clinical Neurology, seizures are most common with glioneuronal tumors like gangliogliomas and dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumors (DNET) (70-80%), followed by low-grade gliomas (60-75%) and high-grade gliomas (25-60%).

“Gliomas are frequent seizure generators,” said UT Southwestern Medical Center neurosurgeon Toral Patel, MD. “Within the glioma family, low-grade gliomas, which tend to occur in younger people [under 50 years of age], commonly present with seizures.”

The Handbook of Clinical Neurology estimates that “approximately 20-50% of patients with meningiomas and 20-35% of those with brain metastases also suffer from seizures.”

“Meningiomas, which are most often benign tumors, can cause seizures as well,” Dr. Patel said. “This is because meningiomas grow from the lining of the brain, and they compress the surface of the brain — the cortex. When the cortex is compressed, it can generate seizures.”

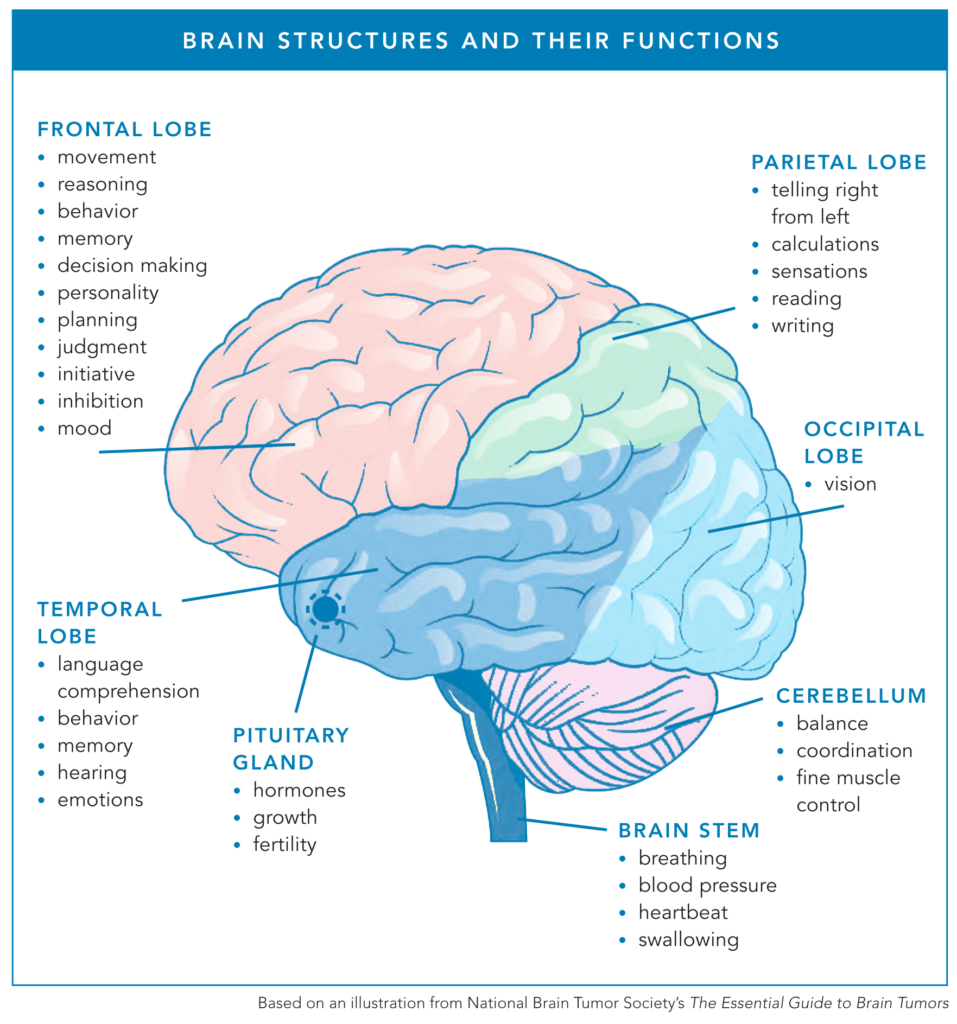

Tumor location also matters when it comes to the likelihood of a patient experiencing at least one seizure due to their brain tumor.

“The temporal lobe, in particular, is an area of the brain that’s very sensitive to irritation,” Dr. Patel said. “Irritation of the temporal lobe has a much higher likelihood of causing a seizure than the same amount of irritation in the frontal lobe, for example. Temporal lobe tumors, as a class, tend to present more often with seizures than similar-appearing tumors in a different part of the brain.”

When are patients with brain tumors most likely to experience seizures?

There are four primary windows in time when patients with brain tumors are more likely to have a seizure.

1. Before or Shortly After Diagnosis

“If a tumor is in a growth phase, it’s more likely to cause seizures,” Dr. Patel said. “Oftentimes, when patients first present to medical attention, especially low-grade glioma patients, they will do so after experiencing a first-time seizure. That’s likely because the tumor was in a growth phase, finally tipped itself over the ‘edge’, and became symptomatic.”

2. After Surgery

“The first several weeks after surgery are also a particularly irritating time for the brain, because you just had an operation, and thus, there is an increased risk of seizures immediately after surgery,” Dr. Patel said. “Long-term, surgery decreases the risk of seizures, but in the short-term right after surgery, there’s a heightened risk.”

3. Long-term Survivorship

According to the Handbook of Clinical Neurology, “approximately 60-90% [of patients] are rendered seizure-free, with the most favorable seizure outcomes seen in individuals with glioneuronal tumors” after tumor removal, also known as resection. However, for some patients, surgical resection does not eliminate their seizures, requiring lifelong management of their seizures.

4. Recurrence

Recurrence is another growth phase when a tumor is more likely to cause seizures because new or growing tumor cells can disrupt normal brain activity or irritate the brain.

What do seizures feel like?

There are many types of seizures that can occur in the brain, so the seizure experience can vary from person to person.

“There are so many different kinds of seizures, and they look different and they feel different for different people,” said Theresa B., who had multiple seizures from an infection after surgery to remove a meningioma tumor. “My right arm would go completely numb, and I couldn’t talk. I was not aware that what I was experiencing was actually a seizure.”

Some patients experience generalized seizures, which impact both sides of the brain at the same time. These seizures include tonic-clonic seizures, formerly known as grand mal seizures, as well as absence seizures, when the patient briefly blanks out and loses consciousness. Other patients have focal seizures, which start in only one part of the brain but can then spread to both sides of the brain.

“I thought a seizure was collapsing, convulsing, and possibly losing consciousness,” said Erica R., who was diagnosed with meningioma in her right temporal lobe. “When I would have a seizure, I would first get an overwhelming feeling of fear. Then I felt as though I was leaving my body. I had a feeling of déjà vu, nausea, felt as if I was losing control of my bladder (I never did), I would get hot, and my heart would beat very fast. I had all of these symptoms at the same time. The feeling was scary, and although I knew it would be over in less than 15 seconds, it felt like a lifetime.”

When a seizure occurs, a layperson can witness a patient having convulsions and know something is wrong, but a focal seizure can be harder to detect. These seizures can look like odd moments occurring over and over again, such as:

- Unusual smells like smoke, but no one else in the room smells anything (known as olfactory auras)

- Seeing kaleidoscope lights in your vision

- Losing the ability to speak for a brief period of time

- Staring spells

- Feelings of deja vu or fear

- Experiencing odd tingling sensations or numbness in a part of your body

“The most important part of identifying seizures that are not obvious is taking a careful history,” Dr. Patel said. “Many things that are somewhat easy for people to explain away, because they’re short and don’t involve dramatic convulsions, may in fact be seizures. They don’t interfere much with quality of life, and naturally, people don’t assume that they’re having seizures. But, if you’re having repeated events with very similar symptoms that you can’t explain or haven’t had a doctor evaluate, then that’s a good time to schedule a visit with your primary care physician and give them your description of the events.”

Tumor location can also influence how a person experiences a seizure.

“Seizures that arise from the occipital lobe can cause changes in your vision, so you may get sparks of light or a kaleidoscope-type vision,” Dr. Patel said. “Seizures in your temporal lobe can affect speech, especially if the tumor is on the left side. Patients may present to their doctor and say, ‘I had an episode where I couldn’t get any words out. I was awake, I was moving, but I just couldn’t speak.’ That would be very consistent with a temporal lobe seizure.”

Lived Experiences

Brain tumor community members generously shared what a seizure feels like to them. Here is a small sample of their lived experiences.

“I had a number of distinct episodes when I was in my sleep. I had an experience of waking up in the middle of the night from a dead sleep, bolting upright, but I couldn’t move — my arms were stuck by my side. I couldn’t breathe. I would hear this super loud buzzing in my ear. My eyes were completely wide open, and I could see my body, but I couldn’t do anything about it. I felt like I was shaking. It was almost like I grabbed onto a live electric wire, and I just couldn’t let go. Then all of a sudden, it would stop, and I would fall right back to sleep. The next morning, I’d wake up, and my head would hurt.

Looking back, I probably should have gone to the doctor, but I just thought I was really stressed out.

Later, I finally had an awake seizure when I was at home visiting family at the holidays. All of a sudden, my head started shaking. I felt like I was making every decision in my life at the same time. It was like a series of plus, minus, up, down, black, white, yes, no. It was like a neurological storm. The last thing I remember was my brother screaming my name before I disappeared. I woke up on the ground with a bunch of EMTs around me, saying I just had a seizure. I said, ‘No, I don’t have seizures.’ I was young, healthy, drank all the kale smoothies, got a ton of exercise — like the last person you would think to experience something like that.” — Dace H.

“He was doing what they call prayer seizures, where both his hands go up and his head drops down.” — David W., Leon’s dad

“In the spring of 2022, I started getting what I would best describe as a severe headache. This started happening after I would sit for an hour or so and then stand up.

Thinking back, ‘headache’ is nowhere near accurate. More like an attack on my brain, instant in its severity, to the point where I would have to stop what I was doing and ride it out. I got to the point of telling people, as I was hunched over, ‘Just a minute, it will go away. It only lasts around 60 seconds.’ The only comparison I can come up with is an ice cream headache in a different spot of my brain, and 10 times worse.

These “attacks” got more frequent and then to the point where I wouldn’t feel right afterwards. After going to the chiropractor, making changes to my diet, stretching, and anything I could think of, I made an appointment with my family doctor and casually mentioned it. She was perplexed but thought it could be related to blood pressure when I stood up; however, before trying any meds, she decided to be safe and send me for an MRI. I was so not worried about it, I went on a Saturday by myself to get the brain MRI done.

By Monday afternoon, I was sitting in a brain surgeon’s office being told I had a golf ball-sized brain tumor, and, other than surgery immediately, there were no options. I was told that the ‘headaches’ I was having were seizures.” — Heidi K.

“My first seizure was at post-op. They were supposed to give me anti-seizure meds during surgery because of where the tumor was, and the anesthesiologist forgot. I was in post-op and had three seizures within a day or two.

While I don’t remember the seizures, I know my head turns and locks, which is part of the seizure starting. After the seizure, I feel absolutely exhausted. I get myself to the floor or bed and just fall asleep.” — Jane S.*

“Three or four weeks after brain surgery, I was feeling relatively normal when, all of a sudden, my right arm got completely numb, and I couldn’t talk. I was fully conscious and aware. I wanted to say something, but I could not make any words. It went on for a couple of minutes, and then I slowly started to be able to say words, but I couldn’t get out what I wanted to, and then the numbness went away.” — Theresa B.

“My husband, Matt, told me that I was talking about nonsensical things on the phone, and I said, ‘No, there’s nothing wrong. Everything’s fine.’ My husband came to my office to find I had no ability to identify who he was, what my name was, my birth date, his birth date, etc. He said that we were going to the hospital because something wasn’t right. I insisted everything was fine, and he said, ‘We’re going. Let me show you in the bathroom. Look in the mirror — your smile is drooping.’ I looked in the mirror, smiled, and said, ‘My smile is fine. I don’t get what the problem is.’

At this point, I felt very detached from myself. I just felt like I was floating along. Once in the ER, they took me for an immediate CT scan, thinking it was a stroke because my words weren’t making sense. When the doctors were putting me into a CT scan, I experienced a grand mal seizure.

My neurologist believes it was just one very long seizure.” — Lora A.

“I started to not feel very good at work, and I had little black spots [in my vision]. I thought I was going to pass out, and when I came to, I was on a stretcher.

After arriving at the hospital, I was having seizures repeatedly. The seizures weren’t like grand mal seizures — the way that people think of them — they were more subtle. I was with it at some points, but I just couldn’t understand. And then other parts, I could not hold it together.

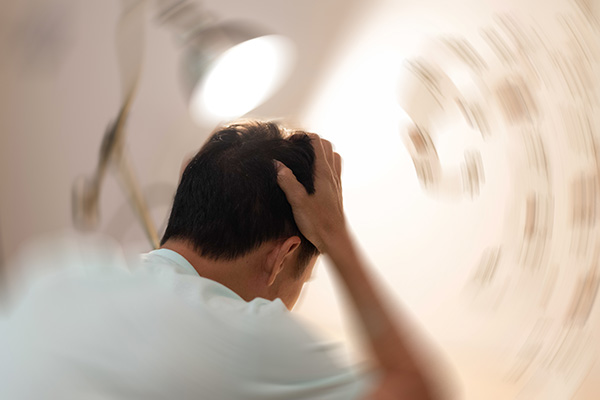

Everything around me was spinning, and I just had to put my head down and let it pass. I felt like I had gone on a ride a zillion times and was ready to throw up because of spinning around so much.

It’s scary in the moment because I can’t express what I’m trying to say, and most people don’t understand. It’s very uncomfortable trying to find words to explain what’s happening, and I just can’t, so it’s embarrassing.

A seizure is very mentally fatiguing. I just don’t want to talk to people after that because I’m still in recovery mode. Physically, even though I’m not shaking, I’m very tense after a seizure. I just want to go home and sleep it off.” — Corinne C.

What is an EEG?

“One part of diagnosing seizures is to take a careful history, but you can’t always be 100% certain based on history alone,” Dr. Patel said. “There can be confounders, and so an objective way to look for a seizure is an EEG.”

An electroencephalogram (EEG) is the brain’s version of an EKG, allowing medical professionals to examine the patient’s brain signals for abnormalities that may suggest irritation of the brain and potential seizure activity.

“Normal brain waves have a pattern and a shape that indicates brain health,” Dr. Patel said. “When you have a seizure, there’s an interruption in that normal pattern and often a very vigorous spiking of the brain waves. Not every seizure, especially short and/or small ones, will generate enough electrical abnormality that an EEG will identify it. That’s because a typical EEG is obtained from the surface of the scalp, and the brain waves have to travel from the brain through the skull, through the scalp, and then get picked up by the EEG electrodes. The surface EEG system is good, but it does not have perfect detection, especially for small seizures.”

An EEG only captures activity during the time the patient is wearing the array. If a patient has a seizure once a day, on average, and the care team happens to place the EEG on for the six hours in between the two seizures, the EEG won’t pick up a seizure.

“There can be small spikes in between seizure events that are indicative of prior and/or future seizures; these are called interictal abnormalities,” Dr. Patel said. “Neurologists will look for those as a sign of global irritation in the brain, but it’s not a definitive indicator that there was a seizure. It tells you that something’s not quite right — where there’s smoke, there’s fire.”

A 48-Hour EEG

EEG tests can range from short 20-40 minute sessions to ambulatory EEGs that can take 1-3 days.

“After I had a number of ‘auras,’ my neurologist recommended a 48-hour EEG instead of doing a short couple-hour EEG in the hopes that they’d be able to capture something during that time period,” Lora said.

Lora opted to do the 48-hour EEG at home, where she was told she needed to spend at least 80% of her time in two rooms because cameras were set up in those rooms for observation. A tech came over to set everything up, including placing the electrodes around her head. Once the EEG was completed, the person returned to gather their materials, and Lora met with her neurologist to discuss the results.

How are seizures treated?

Seizures caused by brain tumors can largely be treated through surgery and medication, with a specialized procedure available to some with treatment-resistant epilepsy.

“Although we typically look to medications for achieving seizure control, and they are critical, surgery does help to push things in the patient’s favor in a big way,” Dr. Patel said. “The data on surgery and seizure control is that if the seizures are coming from a lesion, what’s called structural epilepsy or lesional epilepsy, then there is, on average, a 90% reduction or improvement in seizure control if you remove the lesion. But even after a successful surgery, we still recommend that patients stay on seizure medications for a year after surgery. If there’s been no further seizures after a year, then a trial of weaning off of seizure medications is often appropriate, under the direction of a physician.”

Anti-Seizure Medications

Seizures are typically treated with one of the many anti-seizure medications available that work to prevent or stop seizures. The patient’s care team will recommend an anti-seizure medication as a first-line option based on the patient’s circumstances, moving to other options only as needed. As time goes on, the care team may need to adjust dosing or switch to a different medication.

“All of the medications have some side effects because they are, by design, neuroactive medications. However, compared to some of the side effects from medications that were used 20-30 years ago, we have certainly made a lot of progress,” Dr. Patel said.

Keppra (levetiracetam) is a commonly prescribed drug used to control seizures because it has few drug interactions and doesn’t interfere with chemotherapy. While it is generally well-tolerated, some patients experience significant behavioral side effects, one of which is colloquially known as “Keppra rage.” Side effects can range from mild irritability to severe aggression and emotional instability.

Initial side effects may improve over time as the patient’s body adjusts to the new anti-seizure medication, but that’s not always the case. Patients should communicate all side effects, including behavioral changes, to their medical team to guide decisions about their care. If a medication switch is recommended, the doctor will provide a tapering schedule, as anti-seizure medications should not be stopped abruptly.

“Initially, my anti-seizure medications made me very tired, and it took a long time to adjust to them,” Corinne said. “It’s more normal now as my body has adjusted to it, and I don’t have those same side effects.”

Seizure Rescue Medications

Seizure rescue medications are short-acting medications that can be used to stop a seizure. These medications are available as an oral tablet that dissolves under the tongue, a nasal spray, a rectal gel, and an intravenous formulation for hospital use — all of which allow the body to quickly absorb the medication in seconds or minutes.

Dr. Patel shares how seizure rescue medications can help: “The principle behind seizure rescue medications is that if you’re on a stable dose of a seizure medication that you take twice a day, but every so often, you have a breakthrough seizure, instead of having to up your maintenance dose to such a high level that you start having side effects, perhaps instead, your physician may prescribe you a rescue medication to take as a one off — maybe once a quarter, once every six months, once a year — so that you can get yourself out of the breakthrough seizure without having to increase your baseline medication dose.”

Seizure rescue medications are not taken in lieu of daily anti-seizure medications; rather, they’re a tool aimed at preventing an emergency.

“If I start to feel a seizure coming on, I can take an Ativan like an emergency medicine to help stop it from happening,” Corinne said.

Laser Interstitial Thermal Therapy (LITT)

While removing the brain tumor through surgery and taking anti-seizure medications results in good seizure control for most patients, some people may need to consider an option called laser interstitial thermal therapy (LITT).

“Some tumors will recruit additional networks that are generating seizures outside of the tumor itself, and that’s not uncommon for long-standing tumors that cause seizures, perhaps for many years, in an unrecognized fashion,” Dr. Patel said. “In that case, you can use LITT to thermally ablate those aberrant networks in an effort to achieve tumor control without having to resect all of the seizure-generating brain tissue.”

Laser interstitial thermal therapy is a minimally invasive procedure where a neurosurgeon will take a small laser probe — a few millimeters in diameter — and insert it through a small hole in the skull. Using a navigation system for the brain, the neurosurgeon will put that probe into the lesion, whether that’s a tumor or something that’s causing epilepsy.

Once the probe is inserted into the target, the patient is taken to the MRI machine, which begins generating temperature maps of the brain. Using that real-time information, the neurosurgeon uses the laser to ablate, or heat up, the problematic tissue without delivering a toxic amount of heat to the normal brain tissue.

Patients experiencing treatment-resistant or medically resistant epilepsy will get an EEG workup to determine where the seizures are coming from. If the EEG does not provide the care team with sufficient resolution, they may be asked to perform an intracranial EEG, an alternative to the traditional scalp EEG. In an intracranial EEG, the medical team places electrodes directly on the brain to examine specific areas and identify where seizures originate. If a traditional EEG or an intracranial EEG can localize the epilepsy to a particular part of the brain and determine that it’s coming from one spot, the patient may be a candidate for LITT.

Patients undergoing this targeted treatment will experience less pain than with a craniotomy because the incision is smaller, typically a centimeter or less, and it’s quicker to heal. Dr. Patel finds that most of her patients require only an overnight stay after a LITT procedure, compared with 2-3 nights after a craniotomy.

“Inflammation is very common after LITT procedures, and perhaps even more dramatic than you would have after a craniotomy,” Dr. Patel said. “We have to be very careful about inflammation, and often there is a need for corticosteroids after LITT. However, that inflammation typically subsides quickly. Usually, by one to two weeks after the LITT procedure, the majority of the inflammatory effects have resolved, and most patients will be off of steroids at that point.”

What happens if seizures return?

A breakthrough seizure is a seizure that occurs in a person with a known seizure disorder who has previously been well-controlled on anti-seizure medication. The seizure breaks through despite ongoing medication that had been keeping seizures under control.

“If you start having breakthrough seizures, you absolutely must let your health care providers know,” Dr. Patel said. “If you’re having a breakthrough seizure, it implies that something is changing. It may very well be that something’s changing about the tumor. It could also be that something’s changing elsewhere in your body, metabolically, and it’s affecting the way that you’re either metabolizing the seizure medications or affecting the overall stress levels in your body, either of which could make you more prone to seizures. The key here is that all of this is treatable, and so the only mistake is to ignore it because then you lose the opportunity to treat it. If you’re having breakthrough seizures, there’s almost always a trigger. Something is changing in your body that needs a medical evaluation.”

How can seizures impact quality of life?

Seizures can disrupt daily activities and routines. Not only that, but many states require drivers to be seizure-free for some time before they can legally drive again. (The Epilepsy Foundation provides driving laws by state.) This requirement means an unforeseen seizure can immediately create a loss of independence by taking away one’s ability to drive and leaving the patient entirely reliant on others for transportation.

“I remember the neurologist saying to me that she was going to have to report me so that I would have a restriction on my license,” Lora shared. “I’d lose my license for six months. I remember crying. It sucks, especially if you have a job where you drive for work.”

Additionally, patients may avoid certain social situations due to their concern about having a seizure in public. That worry, along with the inability to drive, can lead to social withdrawal and isolation.

“It has been a big adjustment for me,” Corinne said. “I can’t drive for six months, and it’s a long time not being able to drive and having to rely on the train, the bus, or someone else to drive me.”

Patients may also experience physical fatigue, cognitive fatigue, memory problems, temporary speech difficulties, and other side effects from either seizures or medications.

“About a year or so after the surgery itself, I was diagnosed with epilepsy, so I have to take anti-convulsant medication,” said Julia C., who has a WHO grade 1-2 glial tumor with mixed features. “Anti-seizure medications are kind of notorious for messing with your mood, your appetite, your sleep, and all of that. I do have to deal with the side effects of those medicines, in addition to still sometimes having flare-ups of these seizures.”

In an upcoming blog post, patients with brain tumors will share their tips for navigating seizures.

* Note: This name was changed to protect the privacy of the quoted individual.

The content in this blog post is for informational and educational purposes only. It does not constitute medical advice. Please speak with your health care team to discuss your particular circumstances before making any decisions.