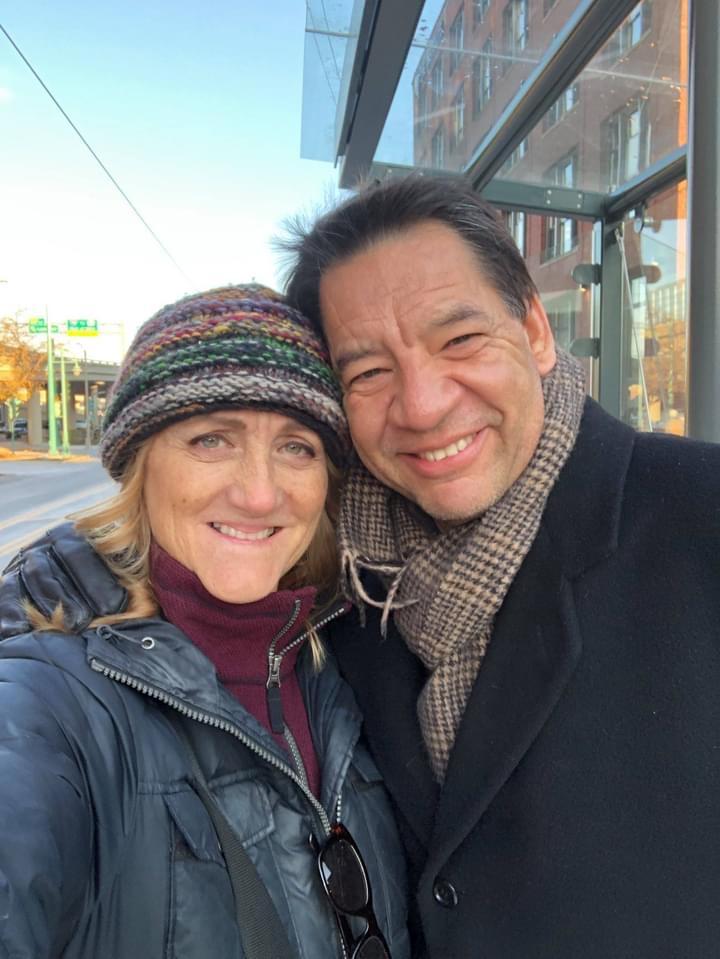

More than 10,000 Americans are estimated to succumb to glioblastoma (GBM) each year. Jeanne Herzog had the inconceivable misfortune of caring for her two favorite guys — her dad and husband — before they passed away from this devastating disease decades apart.

Between Jeanne’s personal experience as a two-time brain tumor caregiver and her professional background as a health psychologist, Jeanne offers a unique perspective on the brain tumor experience, including caregiving and loss.

“In the history of psychology and medicine, we have learned that there are psychological ramifications to illness, injury, hospitalization, surgery, and disability,” Jeanne said. “A health psychologist like me may work with a patient trying to lose weight, a cardiac patient seeking to reduce stress, or a patient dealing with phantom pain.”

Jeanne’s Dad

Jeanne was in grad school studying to be a psychologist when her father, Robert, was diagnosed with glioblastoma in 1997.

“He had been so vibrant before his diagnosis,” Jeanne said. “He loved boating and golf. He had friends. He traveled.”

Before the diagnosis, he suddenly started having trouble concentrating on his bills and would ask Jeanne for help. Later, he hit a curb with his car, which was strange. They discovered the inoperable brain tumor and began radiation.

While Jeanne and her nine siblings were not living at home when he went through radiation, most of the family lived in the same town, so they all took turns caring for him and taking him to appointments. Robert passed away eight months after his diagnosis.

“It was a big loss for our family,” Jeanne said. “I miss him every day.”

Jeanne’s Husband

Twenty-two years later, Jeanne’s husband, Dan, began experiencing nerve pain in his torso. His doctor prescribed an antidepressant that helps with pain, which led to double vision two days later. The neurologist asked Dan to get an MRI, which showed a small white patch in his brain. They continued to monitor and return for an MRI every three months. By the fourth MRI, it had noticeably grown, and the neurosurgeon called it a tumor.

“The doctors at our local place had no solutions for us,” Jeanne said. “We should have asked for a second opinion earlier, but we didn’t think about it. When we did ask for a referral, we were directed to UW Health in Wisconsin.”

During the 10-hour surgery, Dan’s neurosurgeon operated on the part of the brain responsible for speech and language, so the couple knew that he might have some challenges once he woke up.

“The change was immediate after surgery, but it got worse,” Jeanne explained. “Dan took it in stride, but it just made it more difficult. If he had trouble communicating with me, and I wasn’t understanding it, he would cry. He couldn’t perform his job as a psychotherapist and had to change his life. He stopped being able to read, which he loved to do.”

Jeanne looked for opportunities to engage his love for reading by trying audiobooks. Before his passing, Dan would look at the daily newspaper and try to read or have Jeanne read to him.

Loss of Identity

The loss of or change in one’s identity after a cancer diagnosis, can be very challenging. As a health psychologist, Jeanne handled this challenge head-on.

“Most people’s approach would be not to broach the subject of the prior identity lost — don’t remind the person who they used to be or what they used to be able to do — because it will make them sad,” Jeanne said. “My approach is different. I think you have to be OK with getting tears from a person. I think honoring that person’s accomplishments in their identity, what they used to do, and where they went is better, especially if it’s terminal. Getting as much honoring of their life prior to dying is how they die with dignity and knowing that they did right in this world.”

It’s not trying to call out the differences between the pre-diagnosis and current version of themselves; instead, it’s recognizing past accomplishments and supporting them when they struggle with the change in their abilities.

“I think it’s better to talk about it,” Jeanne explained. “It’s better for the person to say, ‘I’m so sad that I can’t do that anymore.’ And then you get to pull them close and say, ‘I know, it sucks. Cancer sucks.’”

Jeanne would then emphasize to Dan what he could do at that moment. For example, she would draw attention to the fact that he made a salad for dinner that evening or watched TV for two hours and knew what was happening.

Caregiving Support

Jeanne’s mother, who was in her late eighties, was diagnosed with cancer about two years before her husband, Dan, was diagnosed with GBM.

“My mother passed away the same day Dan and I went to his surgery consult,” Jeanne explained. “I went from one caregiving situation to another. Because my caregiving situation with each of my parents was stressful but positive, I had a good feeling that I could do it with Dan. This time, however, it was primarily just me. When it’s just the two of you, it’s a full-time job. Even if I could have left him at home, I worried about him 24/7.”

Looking back, Jeanne recognizes the lessons she learned from caring for both parents that she then implemented while caring for Dan until he passed away in April 2023.

“When caring for my dad, I wasn’t very good at asking for help, but people were really good at offering,” Jeanne said. “I got better at asking for support, which was good because I couldn’t leave many people with Dan because of his speech and language issues.”

Jeanne leaned on support in the following ways:

- Reading inspirational books

- Meeting one-on-one with an oncology counselor

- Attending a caregiver support group. “I met some really wonderful women,” Jeanne said. “Their husbands were all sick, some with brain cancer or other cancers, and I have become friends with those people. That helped because even my sisters, the most loving people in the world, don’t know what it’s like and can’t place themselves in my shoes. But the people in the support group can.”

Choosing Gratitude

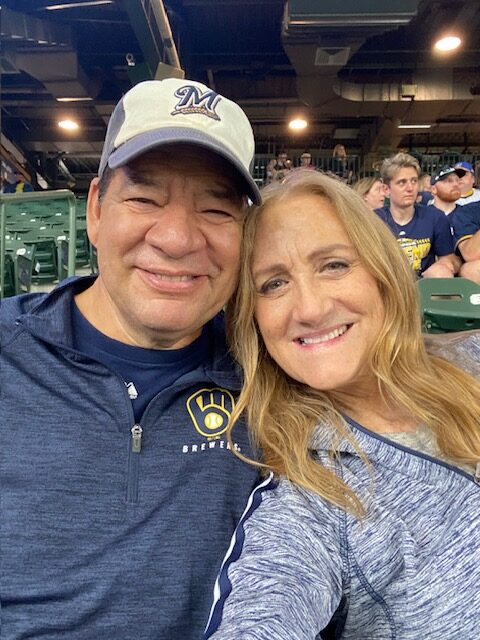

Throughout Dan’s brain tumor experience, the couple learned to live with gratitude, which they called “a gift.”

“I haven’t found the good thing from Dan dying, such as relief, so I keep working on that,” Jeanne said. “We just try to find gratefulness in everything. It’s hard to do when you’re dealing with cancer.”